The Seafly – a potential Cruising Dinghy?

| The following is based on the draft manuscript for an Article which was published in the Spring 2012 issue (DCA Number 214) of the Dinghy Cruising Association. |

In the last issue of Dinghy Cruising there were photos of Gavin Millar and myself enjoying the autumn winds on the River Itchen. I was out sailing my Seafly dinghy single handed in the stiff breeze. Later, back on land, I discussed with Gavin just how suitable the Seafly might be for dinghy cruising.

The one major factor which makes it worth considering the Seafly for dinghy cruising is that, despite being a reasonably fast “racing dinghy”, it is remarkably stable and well behaved. This combination of stability and speed makes it particularly good for day cruising.

If you are caught out in deteriorating weather, or if the wind drops and the current is against you, a Seafly might get you home when others dinghies would fail. Indeed, while the Seafly Class Association (active until the mid 1990’s) emphasised racing, the Seafly was originally conceived in 1960 as a general purpose dinghy suitable for family sailing on the sea.

I first sailed a Seafly as a schoolboy in the 1960’s, not only racing in North Wales regattas, but also day cruising from our home at Llanfairfechan on what then was the “Caernarvonshire” coast. A regular sail was the 9 mile round trip to Puffin Island (visible in photo), off the eastern corner of Anglesey. On very rare occasions we braved the vertical seas in the Penmon Strait tide race and ventured further up the east coast of Anglesey, or head out eastward across Conway Bay to the Great Ormes Head. However careful study of the tide tables was needed for such trips. With spring tides of over 8m, a mistake could mean having to drag the dinghy on its launching trolley half a mile or more across the sands to get home.

The same tide tables suggested that it was easier to sail toward Penmon Point, turn left, and sail southwest along the Anglesey shore to Beaumaris. Sometimes we continued on to the Gazelle Hotel with its own slipway looking out toward Bangor pier. With careful planning one could be stranded in the hotel bar until the tide turned and there was enough water over the Lavan Sands to return home! These trips were normally undertaken by myself and a fellow classmate sailing by ourselves. In those happy days we were brought up under the Swallows and Amazons philosophy of “better drowned than duffers” and, not being duffers, we planned ahead and didn’t drown!

Twice in those North Wales days I was involved in potentially life threatening incidents when racing fleets were suddenly hit by bad weather and boats were wrecked. On both occasions the Seafly got me home safely. Once was a regatta at Beaumaris during the 1966 Menai Straits Fortnight. A sudden gale wrought havoc; some keel boats sank, many dinghies capsized, and both the local RNLI lifeboats and a rescue helicopter were called out. In the Seafly we quickly dropped the main sail and returned to shore under jib alone, planing most of the way. It was so rough that as we passed a GP14 it capsized under bare poles! On occasions like that I was glad I was sailing a Seafly!

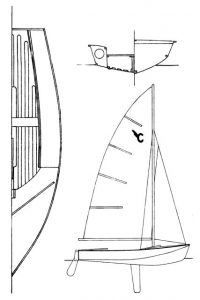

The excellent rough weather performance might suggest that the Seafly is under canvassed; but that is not true. In Portsmouth Yardstick ratings the Seafly is significantly faster than an Enterprise, GP14, or Wayfarer; a useful characteristic if you are fighting your way against a current! The high stability of the hull comes from the way in which the single chine is swept up towards the bow. This creates a “deep V” hull forward with a large, relatively flat planing section aft. Somehow this hull shape also results in a very light helm. The Seafly remains remarkably well balanced on all points of sailing, whether upright or heeled, on or off the plane.

Indeed, it is a very forgiving boat… you can make a stupid mistake when helming a Seafly and not capsize; I know from experience! I’d be brave enough to say that, when cruising, the likelihood of capsizing a Seafly is small. On the other hand, racing, with the spinnaker set in too strong a breeze and the boat almost becoming airborne as it bounces over the waves; well you might indeed capsize! Then sometimes there were problems. The large built-in side buoyancy tanks meant the Seafly floated high and tended to turn turtle. On righting, the boat often contained very little water and floated so high that it was difficult to get back into! But these should not be problems when cruising.

Nowadays I use a mast head float on my Seafly (see photo) and it doesn’t turn turtle. Most Seafly hulls have hatches into the forward part of the side tanks with an internal partition which creates a storage area. The extra weight of cruising equipment in the side tank would make the Seafly ship more water and float lower following a capsize. Reducing the built-in buoyancy in the region forward of the thwart was actually considered by the Class Association and at least two boats were so adapted. This resulted in a “Cruising Seafly” with a roomier cockpit, which was claimed to behave better in a capsize. The large space above the forward buoyancy tank is also available as an alternative stowage space for gear protected in dry bags.

What about over night trips? The relatively flat aft section of the Seafly hull means that it will sit fairly upright on a mud flat or sandbank. Mine lives happily year round at a jetty which dries to mud at low water. However, for over night camping there are aspects where I would think the Seafly would be inferior, for example, to a Wayfarer. The latter is an extra foot longer and has a little more beam, hence a roomier cockpit compared to a standard Seafly. The Wayfarer has floor boards (or a self draining cockpit) giving a relatively flat, dry area for sleeping. In a Seafly you might find yourself lying in a puddle, particularly if self bailers are fitted! The considerable extra weight of the Wayfarer might actually become an advantage if anchored overnight. A racing Seafly with all fittings weighs only 240lb (109kg) and, unless well weighed down by campers and their gear, might be lively when riding at anchor in a gale. On the other hand, hauling a Seafly out of the water and turning it upside down for use as a shelter could actually be contemplated!

What about over night trips? The relatively flat aft section of the Seafly hull means that it will sit fairly upright on a mud flat or sandbank. Mine lives happily year round at a jetty which dries to mud at low water. However, for over night camping there are aspects where I would think the Seafly would be inferior, for example, to a Wayfarer. The latter is an extra foot longer and has a little more beam, hence a roomier cockpit compared to a standard Seafly. The Wayfarer has floor boards (or a self draining cockpit) giving a relatively flat, dry area for sleeping. In a Seafly you might find yourself lying in a puddle, particularly if self bailers are fitted! The considerable extra weight of the Wayfarer might actually become an advantage if anchored overnight. A racing Seafly with all fittings weighs only 240lb (109kg) and, unless well weighed down by campers and their gear, might be lively when riding at anchor in a gale. On the other hand, hauling a Seafly out of the water and turning it upside down for use as a shelter could actually be contemplated!

Although the last original Seafly was built in the early 1990s, secondhand boats in good condition do occasionally come to market and new Seaflys are now being built in the Lake District. My own web site has a history of the Seafly and the Seafly Class Association as well as an attempt to track the whereabouts of surviving boats (both Seafly and Mayfly): www.seaflymemories.org.uk. I’d be happy to talk to anyone interested in using the Seafly for cruising, I can be contacted through the web site.